June 7, 2020, Summer Rooke Chapel Congregation.

The 13th Sunday of Remote Worship

Mark 11:8-11, 15-19

On May 25, 2020, a white police officer named Derek Chauvin knelt on the neck,

of George “Big Floyd” Floyd for eight minutes and 46 seconds. (start a timer.)

Killing him.

Amidst a pandemic that is robbing people – disproportionately Black people –

of life

by stealing their breath.

My good colleague, the Rev. Professor Cheryl Townsend Gilkes,

wrote this week,

that kneeling – in Christian circles,

is an act of veneration.

This murder was a veneration of an American tradition,

of lynching, racism and white supremacy.

This week, our President (Trump – not Bravman),

declared himself the Law and Order president,

and asked that the national guard and active duty military be used to “dominate the streets”

and then proceeded to disperse peaceful protestors,

with tear gas – a substance banned by the Geneva convention –

so he could walk across the street to pose with a bible in front of St. John’s church.

I do not wish to comment upon the President’s private faith.

But I hope – my dear friends –

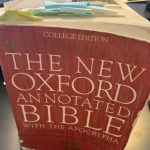

that your bibles look more like this.

And less like that.

And it is clear to me, in this moment,

that our President is spending too much time posing with that bible,

and not enough time reading it.

because, amidst all the important lessons contain therein –

foremost that we are called to love God and love our neighbors as ourselves –

we learn that Jesus was a protestor.

Just a few weeks ago we read the story,

of his arrival into Jerusalem,

mounted on a donkey.

This was

a mass rally of the oppressed and downtrodden.

Crying out “Hosanna” save us.

liberate us from the violent tyrannical forces of the world,

and this was an earthly liberation they were asking for,

at least as much as it was a spiritual one.

And right after,

Jesus enters the temple,

and sees that worship,

has been turned into transaction,

which steals from the poor,

and gives to the empire.

And he got mad.

And he got himself into what John Lewis calls,

“good trouble.”

He made himself a whip of cords,

and he drove away the money changers,

and overturned their tables.

Destroying businesses and livelihoods,

calling them a Den of Robbers.

And the powerful people were afraid of him,

and they looked for a way to kill him.

This was a riot.

That protest,

though it did not remove the emperor from power,

mattered.

And that riot,

though it probably only disrupted temple business at one entrance for a few moments,

mattered.

And Jesus’ final protest,

was his willing march to the cross.

That symbol of empire,

that ancient form of lynching,

that violent, painful, unjust death.

I see people’s eyes being opened right now.

As we witness the lynchings of Ahmaud Arbery, and Breanna Taylor, and George Floyd.

As our attentions are focused on these tragedies

and uprisings,

even as we’re distant from work and travel.

I see people showing up.

And I believe it matters.

And I thank God.

The message of the cross is not – I don’t think – that suffering is redemptive.

If that were the case,

Black folks in America would have long been redeemed.

But rather that suffering can point us to redemption.

out of suffering can come life and hope and liberation.

If we are willing to notice,

allow it to work in us,

and prepared to do the work ourselves.

James Cone wrote in his seminal text,

The Cross and the Lynching Tree

“ Humanity’s salvation is revealed on the cross of the condemned criminal Jesus

and humanity’s salvation is available only through our solidarity with the crucified people in our midst.”

It is in the cross,

paradoxically, that Christians find life.

But only – argues Cone –

if it points us to those who are being lynched and crucified in our midst.

I think it’s fair to guess that none of us gathering here,

or watching online,

will ever kneel on another man’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds. (notice timer)

And fair to guess,

none of us will ever order protestors

(whether we agree with their methodology or not)

dispersed by tear gas.

But what I find myself wondering about,

in these days,

is the other three officers who stood by,

for 8 minutes and 46 seconds.

The dispatchers and shift commanders.

the passersby and teachers and parents and friends.

How many bore witness to this possibility of cruelty,

to this culture and system of racist ideas and policies?

and said and did too little?

In February of 2012, I sat in the Cutter-Shabazz common room,

on the edge of a conversation amongst Dartmouth’s black students, staff, and faculty

(and a handful of allies)

in the wake of Trayvon Martin’s lynching,

by George Zimmerman.

It was, for me, the beginning of a new consciousness,

Our black students were broken by the news.

they were – in that moment, as much as they were anything –

vulnerable black bodies,

in a world that feared them.

I knew them as,

bright, talented, hard-working, successful.

But in that space,

the mask of success cracked,

to reveal people who were, more than anything,

scared and outraged and grief-stricken.

it took a few more meetings, a few more “racial incidents”

some deep reading and learning,

for me to realize that this was a persistent state of reality.

It bore its head unavoidably in the harder moments,

but this fear,

this worry,

this stress,

was there all the time.

Because, of course,

the racism

and injustice are there all the time.

I thought of myself as an ally and an advocate.

I thought I had done the work.

I served on the MLK committee and showed up to rallies,

and spoke – reasonably often – of justice.

I thought myself in a position to meaningfully support,

and care for black students and colleagues.

But I had work to do

and my eyes were opened just a little more that afternoon.

(and I still have work to do)

it’s hard to have our eyes opened.

We will feel guilty, about our blind spots

(or we feel guilt’s twin brother – defensiveness and the need to credential.)

As we come to realize that some of our success might not be due just to intelligence and hard work,

but to inherited wealth,

and unfair structure,

we will worry,

that something of us may be lost.

But the world doesn’t need our worry or our guilt.

It needs our love.

Guilt can be a weigh station.

And we surely need space for confession and lament.

But we must move toward love

Love which looks like compassion and care for our neighbors,

and looks like advocacy for just structures and policies.

Love looks like kindness,

and it looks like challenge.

Love looks like justice and protest,

and generosity, and maybe even, once in a while. a riot

On August 28, 1955,

14 year old Emmett Till was lynched,

by Roy Bryant and TW Milam.

Emmett’s mother, Mamie Till Mobley,

opted to hold a public funeral,

with Emmett’s maimed and brutalized body on full display.

50,000 people attended,

and Jet Magazine carried his pictures around the country and world.

100 days later Rosa Parks – trained and prepared by her NAACP chapter,

refused to give up her seat on a bus,

and the local Women’s Democratic Council

called for a mass boycott of buses.

And asked a 26 year old Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to lead their movement.

What followed was the greatest wave of disruptive action,

and legislative and legal change for racial justice we’ve seen since Reconstruction.

Emmett and Mamie Till mattered.

In 1968, Dr. King was assassinated in Memphis Tennessee,

and uprisings (riots) took hold in virtually every major American city.

A week later the Fair Housing Act was passed,

banning – after decades of work – the refusal to sell or rent property based on protected categories.

Dr. King – and those uprisings – mattered.

And our work – our care, our marching, our speaking out, our advocacy,

matter today.

Because, as Dr. Ibram X. Kendi so forcefully argues,

just as racial progress comes.

Racist progress follows.

We no longer have Jim Crow,

but instead mass incarceration,

We no longer have poll taxes,

but instead voter ID laws,

and shut-down precincts.

This is a moment which demands – not merely our guilt and confession and lament –

but our love and action and bodies and hearts.

Our willingness to change – both publicly and privately.

Our willingness to listen, not to law and order,

but to the voices and experiences of our Black neighbors,

who are leading us toward a more abundant life.

And it matters.

Because on the far side of the cross,

if we pay attention to the bruised and bloodied bodies around us,

is life and liberation,

is hope and beloved community.

Christ is there, awaiting us. Beckoning us.

Singing, perhaps.

Were you there when they crucified George Floyd.

Were you there when they crucified Breonna Taylor.

Were you there when they crucified Ahmaud Arbery, Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, Tony Dade…

Sometimes it causes me to tremble.